fonte: http://www.washblade.com/2003/9-5/arts/feature/hiphop.cfm?page=1

Embracing hip-hop

A homophobic atmosphere pervades the hip-hop industry, but some say the stigma is slowly fading

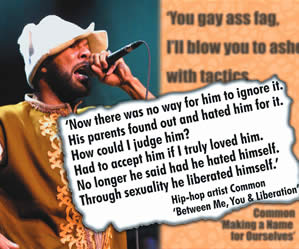

Rappers Common and Eminem are tied for the second most mentions on a list about hip-hop artists who have used anti-gay lyrics in their music. But on a recent track titled ‘Between Me, You & Liberation’, Common soberly tells of a friend coming out of the closet to him, and the emotions he experienced while listening. (Common photo by AP)

Sep 05, 2003

By: RYAN LEE

VISITING “DA DIS LIST” — an online archive of homophobic hip-hop lyrics — it’s easy to see how today’s most dominant urban music genre can be perceived as anti-gay. Compiled by an e-mail listserv known as Phat Family, Da List is littered with lyrics ranging from subtle put downs (“Niggas hate you, they ain’t paying you no attention / In a circle of faggots, your name is mentioned”) to menacing threats (“Your faggot ass better stay to dancing / don’t even look at me, I might break your jaw for glancing.”)

“On the surface, hip-hop is extremely homophobic,” says James Peterson, an English professor who teaches courses on hip-hop at Penn State-Abington, north of Philadelphia. “But beneath the surface, there’s a lot of interesting things going on. It’s an extraordinarily complex social interaction [between gays and hip-hop].”

THE PHAT FAMILY list comes with a disclaimer advising that the 37 examples of anti-gay language on the site don’t come close to representing the complete body of homophobia found in hip-hop lyrics.

“Hip-hop is very anti-gay, and how unfortunate that is,” says Tori Fixx, a Minneapolis gay rapper preparing to release his third album, “black.out,” this month. “It’s sad because there’s literally no respect for these people — us — at all in the music.”

From its inception, hip-hop has been branded as being misogynistic and homophobic, perceptions fueled largely by the hyper-masculine lyrics and personas of mainstream artists.

A bedrock element of hip-hop over the past three decades has been emcees battling one another, searching for the most degrading verse to defeat an opponent. One of the least original forms of dissing another rapper is to challenge his manhood by calling him a “fag.”

“Some of that is homophobia, but because it’s such a masculine culture, gay terminology is used to denote any kind of negative,” says Peterson, who also is media coordinator for the Harvard University-sponsored Hip-hop Archive Project. “It’s not necessarily being explicitly anti-gay.”

Many gay rap fans are “linguistically savvy enough to know that some of these terms are not targeting them,” Peterson says.

Fixx partially agrees.

“If an artist calls another artist a punk or a faggot in a song, then moves on, then that’s just beef with that person,” Fixx says. “But if the artist is mentioning punks or faggots as a whole and is discussing or promoting violence of any kind, that’s different and one should be offended and stop supporting that artist.”

THE OUTRIGHT PERSECUTION gays experienced in hip-hop has diminished considerably, according to Reggie Thomas, a promoter at Club 708 in Atlanta who has been promoting black gay clubs for the past 12 years.

“Some of the earlier stuff mattered because it was specifically directed toward the gay crowd,” he says. “But it’s really not a big issue now because the artists may say something, but it’s not as harsh as it used to be.”

Nevertheless, the majority of hip-hop artists — particularly males — are keeping their gay fans at arms’ length.

Local rappers in Atlanta turn down opportunities to perform at Club 708 so often, Thomas says he’s stopped asking.

“They’re not going to do it because of their reputation,” he says. “They won’t do it anytime they know it’s a male gay club.”

This stigma against gays in hip-hop is a by-product of a general discomfort with gays among some African Americans, Fixx says.

“What many people don’t realize is that homosexuality is not accepted in the black and Hispanic communities,” he says. “Being that hip-hop is predominantly made up of black and Hispanic artists, homosexuality won’t be accepted or respected in the music any time soon.”

WITH FIVE SONGS each, rappers Common and Eminem are tied for the second most mentions on Da Dis List. But a second disclaimer on the list seems to speak directly to these two artists.

“In the interest of fairness,” the Web site states, “it should be noted that some of the more blatantly homophobic quotations are from early in certain rappers’ careers, and do not necessarily represent the artists’ current views on homosexuality.”

Eminem curried a certain level of forgiveness for his early anti-gay lyrics when he performed with gay pop star Elton John at the Grammy Awards in 2001, although Eminem was still boycotted by the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation.

The outspoken rapper likely learned from previous victims of organized gay protests — from Donna Summer to Dr. Laura — that it’d be better for his career to avoid homophobic lyrics, says Lisa Cox, founder of “Girls in the Night,” a lesbian party circuit in Atlanta.

“He’s changed his tone and turned it down a lot,” she says. “The gay market is extremely powerful and can make or break any artists.”

On his latest CD, “Electric Circus,” Common seemed to repent for the anti-gay lyrics he regularly spewed on his first four albums, including, “Homo’s a no-no, so faggots, stay solo” and “I’ll turn you into the artist formerly known as You gay ass fag.”

On the track titled “Between Me, You & Liberation,” Common soberly tells of a friend coming out of the closet to him, and the emotions he experienced while listening.

“So far we’d come, for him to tell me / As he did, insecurity held me / ’Til his spirit yelled help me,” Common rhymes. “How could I judge him? Had to accept him if I truly loved him / No longer, he said, had he hated himself / Through sexuality he liberated himself.”

Common’s reputation as a street-turned-bohemian artist grants him a creative license to explore issues others are afraid to take up, according to some hip-hop experts familiar with his work.

Although his conscious lyrics may not appeal to younger listeners, Peterson said Common’s new direction about anti-gay lyrics is “a big turning point.”

“I think it teaches the mature fan base about how things work, and that’s what we need: We need to see our artists mature and we need some things explained,” Peterson says. “I think it’s a great story to tell and it’s really a model for a lot of artists out here on how to evolve and grow.”

LESBIANS HAVE MADE even more headway into hip-hop, probably because of the girl-on-girl fantasy endorsed by even the most anti-gay artists, according to Cox.

“Back in the day, we couldn’t get an artist to do a girl party to save our life,” Cox says. “But now we have earned the respect of the recording artists and they recognize they have to embrace all of their fans.”

“Girls in the Night” recently was scheduled to play host to a party at BarCode in downtown Atlanta featuring Big Gipp from the rap group Goodie Mob. Female rapper Da Brat was to perform at another club.

When New York-based gay rapper Caushun began appearing in urban magazine articles and on MTV, it seemed barriers around hip-hop were about to be torn down.

But two years later, little has changed.

“The media focused on his title, not his music,” Fixx says. “No music surfaced, so I think that hurt us more than it helped. It’s almost like the media wanted to make a joke about it, and they missed the boat entirely.”

Caushun was thrust into the position of spokesperson for gays, something he was not ready for, Peterson notes. Yet despite the rough start, Peterson, Thomas and Fixx agree that it is just a matter of time before an openly gay rapper emerges, becomes successful, and puts another dent in the stigma.

“Once one gets out there, it will become like the Eminem thing — the ‘white rapper syndrome,’” Fixx says. “Everybody will be trying to grab the next big thing.”

——

Phat Family web site — http://www.phat-family.org/